The Hine’s Emerald Dragonfly eggs that GNFH has been housing since the end of December have all hatched. The eggs were held at 39-41 degrees over the winter and, in early April as the outside temperatures began to rise, we began warming the eggs. By end of April they had warmed to 60 degrees, and almost 1000 larvae had hatched. Egg cups were checked every day, and the day’s newly hatched larvae were placed in small specimen cups of pond water with a few zooplankton items as food.

These juveniles were then distributed into small rearing cups either individually or in groups of two or three individuals per cup. These cups, kept in groups by maternal line, are being housed at 60 degrees and fed three times a week by pipetting pond water with concentrated zooplankton filtered out of the pond water that comes through the mussel building. Food water is checked for larger pests that will view the dragonflies themselves as food (for example chironomids, some species are predatory). The remaining copepods, ostracods, cladocerans, and an early April bloom of rotifers- which appear to be a preferred food for new instar larvae- are available for the little dragonflies to hunt as prey.

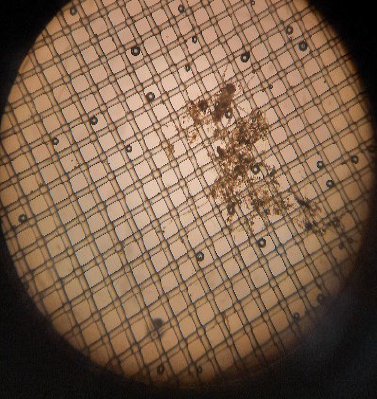

After the larvae grow past their first few instars in these protected cups, they’ll move up to the next stage- small pvc and mesh cages submerged in a larger volume of water, with more food available. Individuals have to have grown large enough to stay enclosed in mesh with 500-micron openings—this size is large enough to allow water flow to bring in oxygen and new food items in without clogging too quickly the our productive pond water with algae and detritus. The photos below (bottom row) show an early and later instar juvenile on this screen as a check to see if this mesh size will contain the individual (answers: not yet, and yeah, definitely!).

By: Beth Glidewell

A three week old and 5 month old dragonfly larva on the same size mesh screen. Photos: Beth Glidewell/USFWS.